Case File #17 – Detective Octavius Pinot in “The Auxerrois Affair”

A Spark from Burgundy

Burgundy had been crafting its golden-hued white Burgundies for centuries — wines that seduced kings, popes, and enough wine merchants to fill a cathedral.

By the late 1970s, South African winemakers were tasting these treasures for themselves. At that time, they weren’t absurdly priced; a bottle could be had without selling your bakkie.

But as they sipped and sighed, they knew they were stuck. The grape behind these masterpieces — Chardonnay — was absent from South African soil. And the mighty KWV (affectionately nicknamed the KGB of the Winelands) would take up to 15 years to approve a new varietal.

In the small, tight-knit world of Stellenbosch, Paarl and Robertson, news of this glorious grape spread like wildfire. And as often happens in the wine trade, admiration quickly turned into action.

Somewhere, someone decided: if we can’t import it, we’ll just have to… acquire it.

Octavia Case Note: In the late 1970s, legal Chardonnay plantings in South Africa were negligible. The KWV controlled all new varietal imports, and approval could take more than a decade.

Suitcases and Swaziland

Narration – Octavius Pinot

Every smuggling tale has its signature move. In this one, it wasn’t trench coats or false passports — it was battered Samsonites.

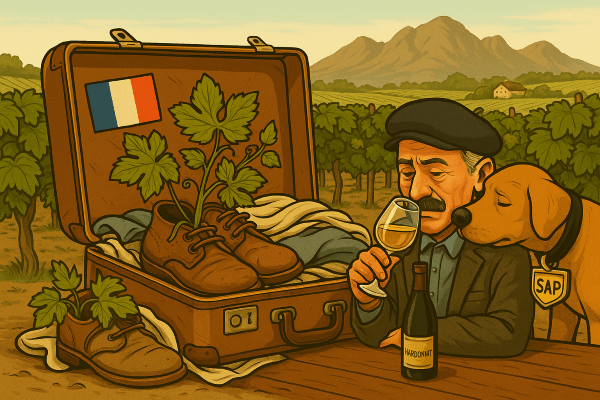

The veterans still chuckle about it over a glass: cuttings from Burgundy, lovingly wrapped in wet newspaper, tucked deep inside an old pair of veldskoens. Sometimes they were slipped between shirts that hadn’t seen an iron since the Carter administration, their musty aroma designed to ward off the beady eyes — and sensitive noses — of customs officers at Jan Smuts Airport.

But not every courier had the nerves for a direct drop. That’s where Swaziland came in. The cuttings would be spirited across the French border, survive the long haul to the Lowveld, and take a short holiday in Swazi soil. There, they’d rest in black nursery bags, multiplying quietly until the day they could cross the SA border under less scrutiny.

The Propagation Plot

Once back in the Cape, the vines found discreet homes — sometimes in experimental vineyard rows, sometimes hidden behind windbreaks as if they were part of someone’s personal garden project.

They stood in neat lines, swaying gently in the breeze, blissfully unaware they were part of an agricultural crime scene.

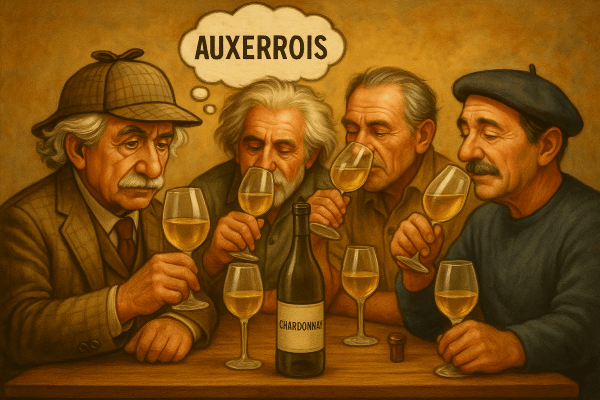

Here’s the catch: vines are great at keeping secrets. Some were the genuine article, true Chardonnay, destined to make wines that would cause judges to swoon. Others were imposters — Auxerrois or Olasz Riesling — dead ringers to the untrained eye. Even seasoned viticulturists had to wait until harvest to know the truth.

Octavia Case Note: Some of the earliest “Chardonnay” in SA was later identified as Auxerrois or Olasz Riesling — cultivars similar in appearance but different in wine style.

The Blind Tasting

The first “Chardonnays” appeared around 1980. Proudly labelled, poured into glasses, and swirled with reverence.

In one tasting I attended, the room was thick with buttery aromas and the murmurs of contented judges. The verdict seemed unanimous: a triumph.

But when I took my first sip, my palate twitched. Something was wrong. The acidity was softer, the fruit profile a little… northern. I leaned back in my chair and muttered into my moustache:

“Auxerrois.”

A waiter dropped a tray. Someone coughed. The air suddenly tasted of suspicion.

Octavia Case Note: Before DNA testing, vines were identified by ampelography — the study of leaf shape, bunch form, and shoot growth — a method not foolproof for closely related cultivars.

The Trophy Trouble

A few years later, one of these “Chardonnays” won gold at a prestigious international show. The Cape wine industry beamed. Press releases flew. Champagne corks ricocheted off tasting-room rafters.

But in the quiet corner of the banquet hall, a discreet conversation unfolded. There was talk of… re-engraving the trophy. Of labelling “adjustments.” Of pretending the whole thing had been intentional.

After all, you don’t pour out a gold-medal wine just because it’s not quite what the label says.

The Klopper Commission

Eventually, the whispers reached official ears. The Klopper Commission was convened: a stern-faced parade of inspectors, scientists, and government men who looked like they’d never smiled at a wine in their lives.

They collected cuttings, examined vineyards, and shuffled a great deal of paperwork.

And then? Pardons all round.

The conclusion was as smooth as a barrel-fermented vintage: yes, there had been smuggling, yes, there had been misidentification, but the wines were excellent and the world was applauding. Case closed.

Octavia Case Note: The Klopper Commission investigated vine smuggling and misidentification in the mid-1980s. No penalties were issued, and Chardonnay plantings grew rapidly afterwards.

The Case Goes Cold

By the late 1980s, Chardonnay plantings had exploded. The official clones were finally approved, but by then, the smuggled vines had already written their own chapter in South African wine history.

As for me, Detective Octavius Pinot, I still keep one of those original cuttings in my bottom draw.

And every now and then, I give it a nod — a salute to the winemakers who decided that sometimes, to make history, you have to pack a Samsonite.

Leave a comment